Timbisha/Death Valley, Part 1

Friday-Saturday, 15-16 March, 2019

Eric's photo of the two of us together in the extreme environment of Badwater Basin, the lowest point in North America, kneeling in salt with snow above us.

Our romantic relationship began on 16 March, 1989, at a very silly Easter egg-coloring party that Mark and I hosted. To celebrate the thirtieth (Wow!) anniversary of this momentous event in our lives, we chose to add another national park to our list, the only one in California we had not yet visited--Death Valley. Everyone made jokes when I told them we were going to Death Valley to celebrate what we call our "coupleversary," so let's call it instead by the name that the indigenous people of the area call it, Timbisha. The indigenous elder interviewed for the Park Service's film tells us that the valley is very much alive.

Getting There

How can we possibly have overlooked Timbisha for so long, lived in California for almost 26 years and have one of its national parks in which we'd never set foot? It's remote! Very remote. To drive from Berkeley to Furnace Creek, the central area of the park with most of the attractions, took nine hours.

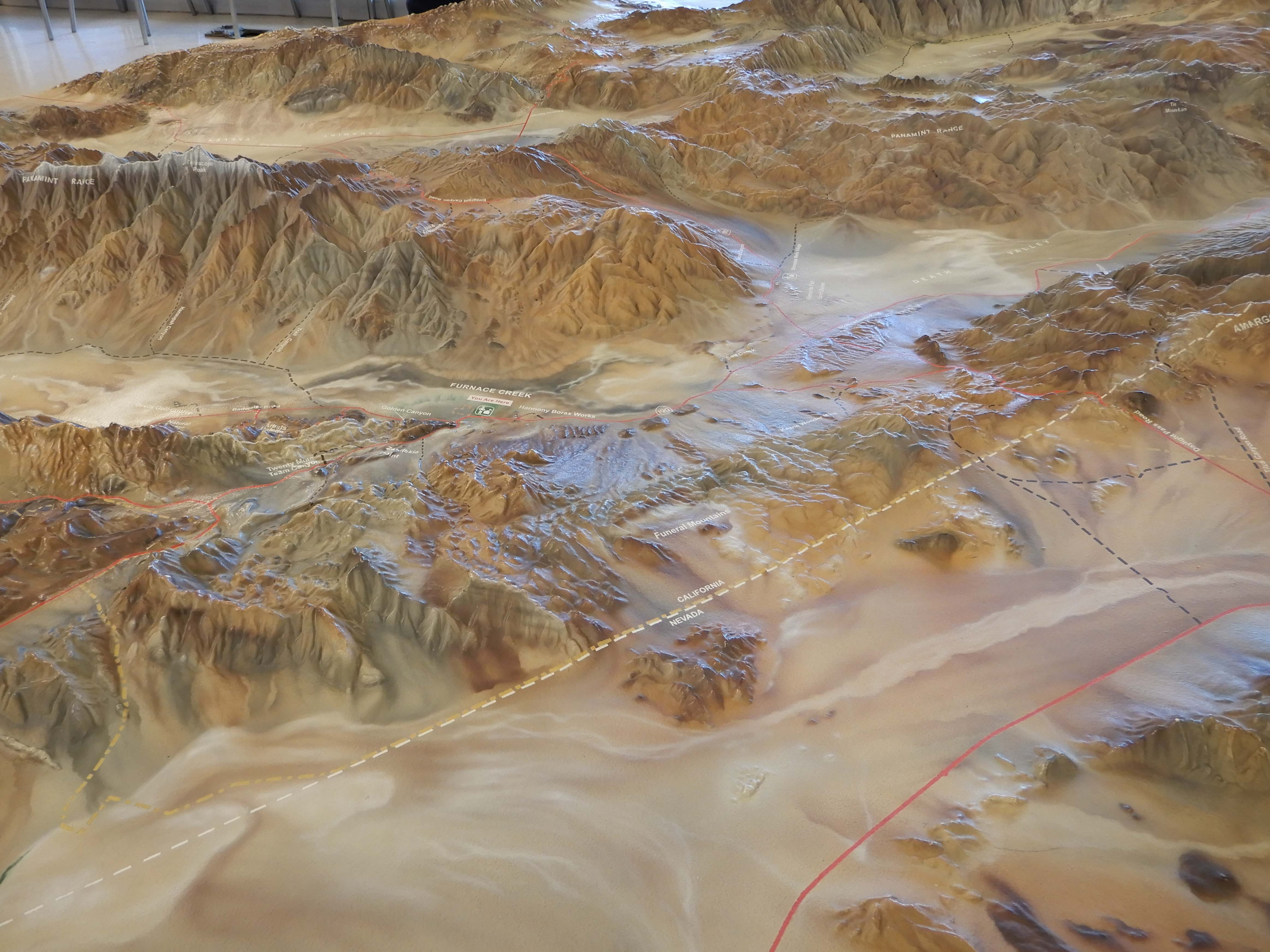

Why does it take so long? Timbisha is in the geologic Basin and Range province that fills most of Nevada. Although most of Death Valley National Park is in California, it is closer to Las Vegas than it is to Los Angeles or San Francisco. The crust is stretching and thinning here, like a pizza crust, as the Sierra Nevada to the west and the Rocky Mountains to the west spread apart from each other, creating a series of mountain ranges with valleys between them. The central part of the Sierra is the highest part, and no roads cross it, so you have to drive all the way south to Bakersfield and then come back north toward Las Vegas. Then you have to cross into the Basin and Range and start bouncing over ranges and into basins. It's hard on the eardrums. Timbisha lies between the Panamint and Amargosa Ranges.

The driving is like this.

CA Highway 190 heading up into the Panamint Range. Photo by Eric.

Eric took a picture of the relief map at the Visitor Center showing the Basin and Range topography.

So, we spent many hours in Mather, driving through oddly verdant Central Valley hills.

We crossed to the east side of the Sierra, where we could look see its snow-capped ridge peeking through closer mountains along US Highway 395.

Even though we left Berkeley before 6:00, it was 13:25 before we reached the park entrance sign. Since we were celebrating our coupleversary, we posed for the iconic picture together.

Around 14:00 we passed Panamint Springs, where we would sleep the next two nights, and it was 15:00 before we reached Furnace Creek, site of the park's most major attractions. Logistics play a major role in any national park visit, and they play an outsized role in a visit to Death Valley National Park, as it is an outsized park, the largest in the continental United States. We had selected Panamint Springs to save money and avoid camping in harsh weather conditions. But, while Panamint Springs is technically inside the park, it is not well placed for a park visit. Our recommendation is to shell out the money for lodging in Furnace Creek, rather than spending quite so much time in the comfort of your air conditioned vehicle. While driving on CA Highway 190 is actually rather fun, you probably wanted to spend more time actually exploring Timbisha's beautiful desert sites.

Artists Drive

I had been looking forward to Artists Drive, a one-way road through hills covered in brightly-colored mineral deposits, but it had been closed due to flooding and debris two days before our visit. Fortunately, the ranger at the Visitor Center told us, the Park Service had reopened the drive.

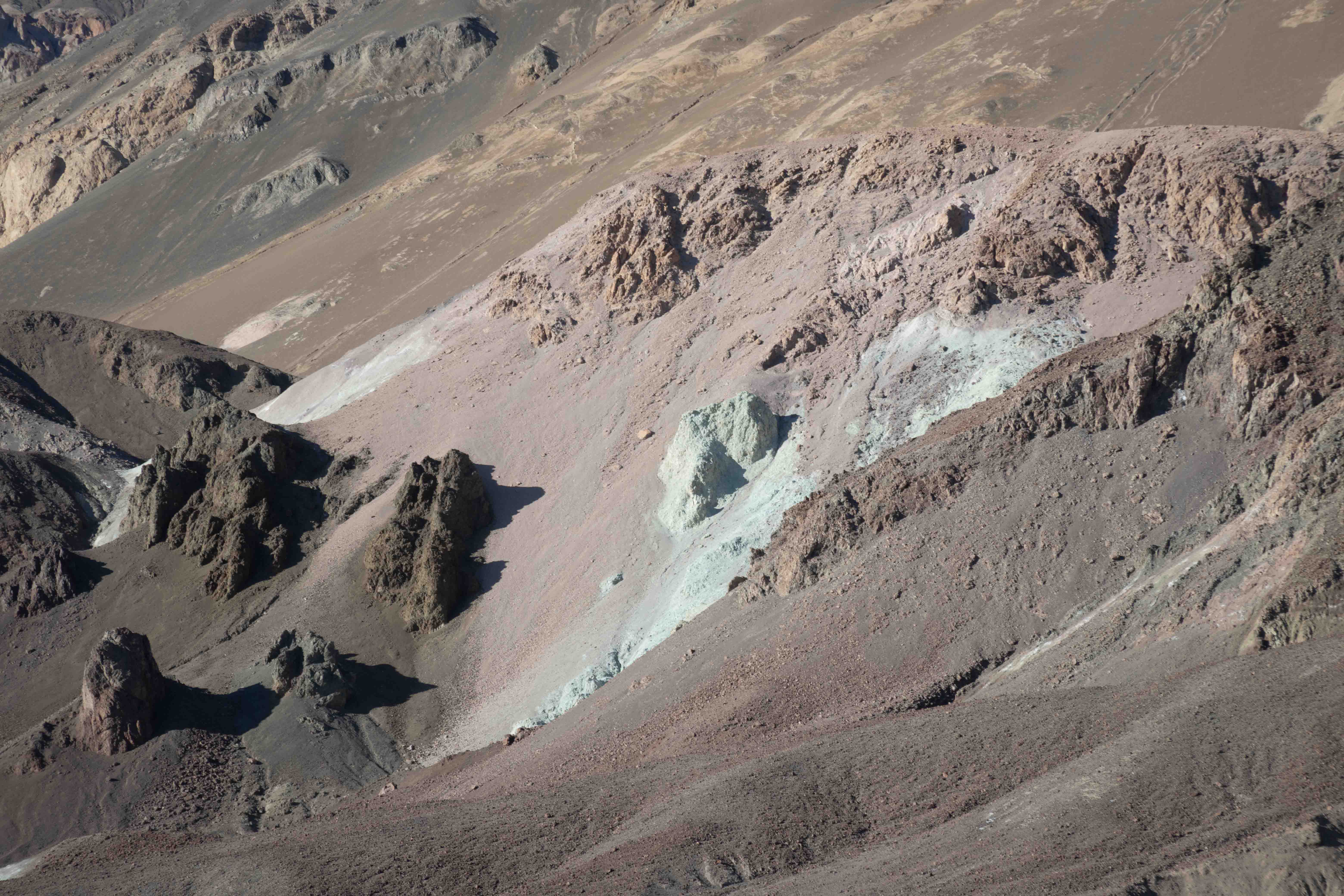

I bought Geology of Death Valley by Marli B. Miller and Lauren A. Wright at the Visitor Center. It told me that the area in the photograph below showed a fault surface, with striations indicating the line of the slip.

Artists Drive.

The highlight of Artists Drive is colorful Artists Palette, which looks a little bit like ice cream.

Geology of Death Valley says that the colors typically all come from iron; it's just that the reds and purples come from oxidized iron and the greens come from reduced iron.

Eric took a pictures of the wash (dry streambed) running through Artists Palette.

The two of us together as photographers at Artists Palette.

We had an early dinner at the Timbisha Shoshone Village. I think it's good to patronize native businesses, and the ranger told us it was the fastest and least expensive alternative around Furnace Creek. They serve tasty tacos on a traditional Timbisha fried bread.

Zabriskie Point

We headed for Zabriskie Point, the most iconic viewpoint in the park, for the sunset. But we didn't realize that the sun would set behind the ridge before the astronomical sunset, and we arrived too late. Photo by Eric.

Geology of Death Valley tells us that Zabriskie Point is an excellent example of badlands topography, which is created by water erosion of poorly consolidated rock materials with little or no vegetation growing on them and holding them together. It typically results from sudden cloudbursts rather than regular rainfalls.

Eric photographed the red rocks.

Dramatic layers at Zabriskie Point.

Early in the week, The San Francisco Chronicle published a beautiful and dramatic photo of a temporary lake at the bottom of the valley at Timbisha. I had doubted that it would hold out for our arrival before it evaporated. It hadn't evaporated entirely, but not much remained.

Even without the lake or the magic light of the sunset, we still enjoyed the dramatic badlands topography.

Hills above Zabriskie Point.

We find it interesting that we had never seen badlands before last May, when we made our first visit to the Colorado Plateau. Since then, we've made two more forays into this sort of desert topography, to Anza-Borrego Desert State Park last December, and now into Death Valley National Park. We've become fascinated by waterless landscapes.

Mesquite Dunes

As we had risen so early Friday morning in order to spend some time in the park that day without paying for a motel room for Thursday night, we were already on the early schedule, and so thought it wouldn't be too terrible to get up for a Saturday sunrise shoot. This would also get us out hiking earlier in the day, when it would be less hot, as our location far out in Panamint Springs made it impractical to spend the hottest parts of the day napping in our room. Fortunately, temperatures were only predicted to rise into the mid-80's F, high 20's C. We chose the Mesquite Dunes for the sunrise, as they were a bit more than halfway between Panamint Springs and Furnace Creek, near a tiny settlement called Stovepipe Wells.

Classic view of windswept Mesquite Dunes. Photo by Eric.

Eric took a picture of salt collecting at the bottom of the dunes. The Park Service's movie told us that the mesquite plant can send roots down 150 ft/50m to find water.

Eric captured the first light on the hills over the dunes.

Sun on hills.

Early sun striking dunes and hills.

Early sun on the dunes. It was difficult to find pristine dunes unmarked by footprints.

Eric's view.

Patters on sun and shadow on dune ridge.

Frustrated by the difficulty of cropping other photographers and their footprints out of my frames, I found more satisfaction in taking abstract macro photos of the sand.

R2D2 was filmed rolling away from a hand-wringing C3PO after their crash here at Mesquite Dunes. We found a Tatooine-themed earthcache, as part of the purpose of this trip was to check remote and coveted Inyo County off of our geocaching list. Wikipedia also tells me that the Sandcrawler was filmed on Artists Drive, and that the Tusken Raiders were filmed mounting Bantha at Desolation Canyon.

We had a breakfast buffet in nearby Stovepipe Wells. The friendly waitress who checked us out told us that, since we were staying in Panamint Springs, we should see Darwin Falls there. We decided to see as much as we could in Furnace Creek on Saturday, and avoid spending the two-plus hours to drive back on Sunday. We would have to save Dante's View of Timbisha for a future trip, but have a more relaxing vacation this time.